Director Kirby Dick's "The Invisible War" was one of the most acclaimed – and influential – documentaries of 2012. It illuminated the pervasive incidence of rape in the military and near total lack of justice for victims. It has sparked an ongoing movement for reform, and it's been nominated for an Academy Award. So why, then, are two of the rape survivors who appeared in the film speaking out now about how "betrayed" and "abandoned" they feel, not by the military that left them vulnerable to sexual violence, but by the filmmakers who told their stories? It's because these victims are men – and they say their story has not been adequately told.

Michael Matthews, the Air Force veteran who shared his story of being gang raped in 1974 in "The Invisible War," complained to NBC News this week about the lack of male presence in the awards season promotion of the film. "They don't list any of the men on the website," he noted. "[Dick's] making millions of dollars but he's not bringing any of the men to any of these appearances all over the country like he's bringing the women." (The publicity images from the film are undeniably female-centric, but Dick denies he's "making millions" off the movie.) Matthews continued, "I appreciate them putting us in the movie but, now, the men are not being represented at all. He has turned his back on us. And the movie, some of it, is hurting us." Navy vet Brian Lewis, who was raped by a senior officer in 2000, agreed, adding that he's disturbed by "the film's fleeting attention on male victims."

"The Invisible War" is based on writer Helen Benedict's unmistakably gender-specific 2007 Salon feature "The Private War of Women Soldiers." That's why, when I saw the film the first time last spring, I was grateful that Dick and company had expanded the sweep of the narrative to include the often-taboo topic of male-on-male rape. And it seemed clear the filmmakers had make extra effort to find men willing to speak out on the subject, especially given that one of the victims' experiences dated back almost 40 years.

Hard data on rape is always difficult to obtain, because such a large number of crimes go unreported. It's even trickier when the subject is male rape, because of the stigma and misunderstanding frequently surrounding the topic. It was only last year that the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Report revamped its definition of rape beyond "the carnal knowledge of a female, forcibly and against her will" to include, among other things, rape of a man. At the time, clinical psychologist David Lisak told the New York Times, "We have a cultural blind spot about this. We recognize that male children are being abused, but then when boys cross some kind of threshold somewhere in adolescence and become what we perceive to be men, we no longer want to think about it in this way."

The National Institute of Justice estimates 3 percent of men have been raped, while for women the figure is closer to 17 percent. For military men and women who've applied for disability benefits for PTSD, though, those numbers are much higher – "6.5 percent of male combat veterans and 16.5 percent of noncombat veterans reported either in-service or post-service sexual assault." But for women, the figure can soar as high as over 86 percent.

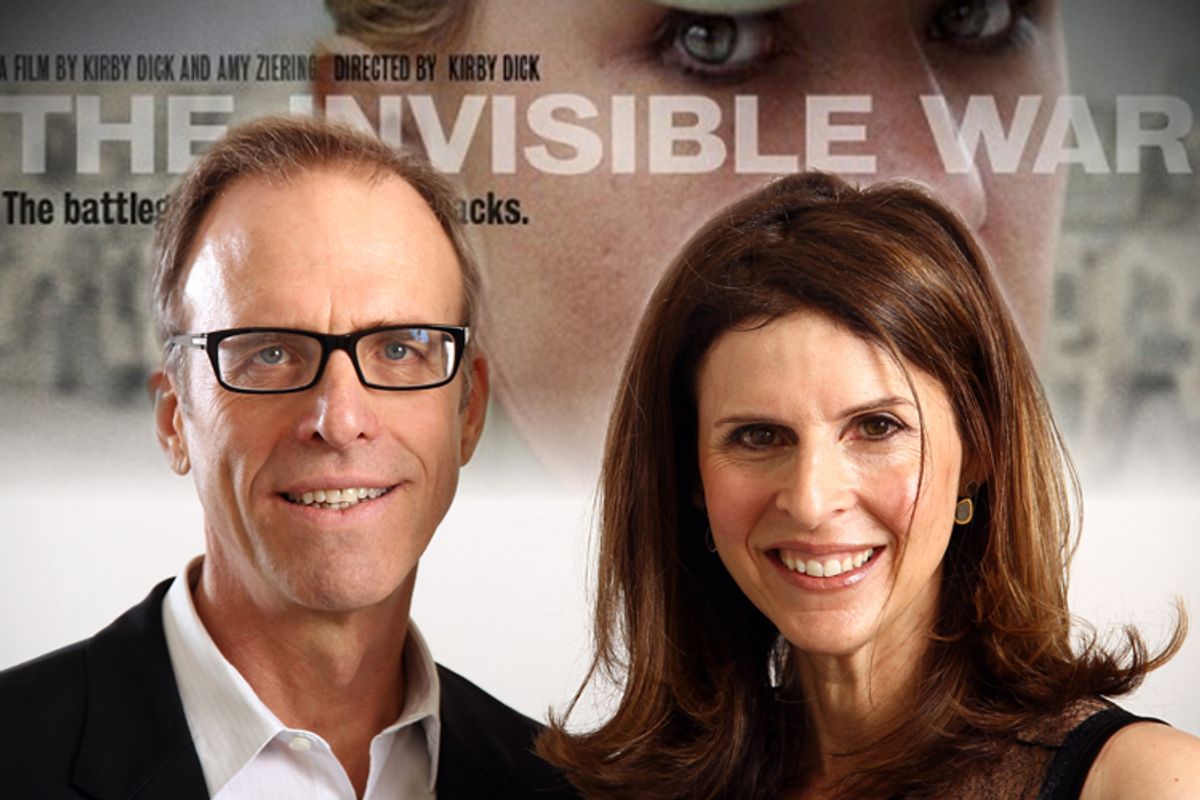

Ultimately, it's an act of continuing bravery for the filmmakers and for Michael Matthews and Brian Lewis in particular to keep talking about the issue. The need to pay serious attention and have sensitive, open conversations about the problem of male-on-male rape in the military, and the devastating aftereffects, is genuine and pressing. But given the statistics, it would have been unusual for the ambitious, expansive "Invisible War" to devote much more of the story to an issue that affects a much smaller proportion of rape victims. This week, Kirby Dick told NBC News, "We owe these men a great deal of gratitude for coming forward. These are the true whistle-blowers." And he added, "Our essential goal here is to have the military continue to change its policy … so that all men and women are protected in the military."

Shares